|

There it was again, that vexing discord between the E string of the first violin and the C string of the cello, robbing quartet rehearsal time and provoking a grand rethinking of fingering and tuning. After years of experiment and countless hours spent in Intonation Hell, the ensemble settled into the solution of tuning with slightly compressed fifths, in effect borrowing from the keyboard's equal temperament. We found that the frequency and severity of our discussions were diminished by at least 50 percent. Administratively speaking, we were way ahead in efficiency but were troubled by the drop in product quality.In discussions with colleagues in other quartets, the dominant opinion was that we were hammering our beautifully rounded instruments of infinite color into the square holes of the Grand Compromise. I found a deep-seated distaste for equal temperament. In the mythology of music performers, the intonational Good Guys are invariably the Just, relentlessly battling the mechanistic conformity of the evil Storm Troopers of the Tempered.

Sound Numbers

There is no mystery to Just intervals, objective mathematics and subjective judgment concur. Given any two notes in a contextual vacuum, the ear will strive to tune them to a Just interval. The Just scale plucks its notes from the upper partials of a tone's harmonic series. All notes in the series lie in a peaceful, mathematical repose. When played or sung together, the resonance of the combined notes tend to support each other, ringing true without any beating.

The Just scale, however, is unhinged by its own perfection. Scales built on one fundamental will not fit with notes of another fundamental. This effect becomes very clear when the results of the intervalic ratios on different notes are compared. The ratios of successive notes in a diatonic major scale are: major second, 9:8; major third, 5:4; perfect fourth, 4:3; perfect fifth, 3:2; major sixth. 5:3; major seventh, 15:8; octave, 2:1. The Just scale, however, is unhinged by its own perfection. Scales built on one fundamental will not fit with notes of another fundamental. This effect becomes very clear when the results of the intervalic ratios on different notes are compared. The ratios of successive notes in a diatonic major scale are: major second, 9:8; major third, 5:4; perfect fourth, 4:3; perfect fifth, 3:2; major sixth. 5:3; major seventh, 15:8; octave, 2:1.

Figure 1 shows the values for the scale in vibrations per second, beginning with A440. If the same formulas are applied beginning with the B that is the second step of the A major scale, some very different notes with the same name result. (Compare Figure 1 with Figure 2.) Figure 1 shows the values for the scale in vibrations per second, beginning with A440. If the same formulas are applied beginning with the B that is the second step of the A major scale, some very different notes with the same name result. (Compare Figure 1 with Figure 2.)

This discrepancy is not a problem for stringed instruments until performers attempt to build chords with open strings, clearly demonstrated when the ratios are applied to open strings. Perfect fifths would give the values of: E, 660; A, 440; D, 293.33; G, 195.56. Continuing to the viola, the C string would be assigned a value of 130.37. (For those of you following along at home, a small degree of rounding in these numbers may give you slightly different results.) Halving the value of the viola C means a C of 65.19 vibrations per second (vps) for the cello. To generate an E one major third above this lowest C, apply the ratio of 5:4 to get an E of 81.48 vibrations. Transpose this up three octaves by multiplying by eight and the result is 651.85 vps-hardly a comfortable fit with the 660 vps in the violin. This discrepancy is not a problem for stringed instruments until performers attempt to build chords with open strings, clearly demonstrated when the ratios are applied to open strings. Perfect fifths would give the values of: E, 660; A, 440; D, 293.33; G, 195.56. Continuing to the viola, the C string would be assigned a value of 130.37. (For those of you following along at home, a small degree of rounding in these numbers may give you slightly different results.) Halving the value of the viola C means a C of 65.19 vibrations per second (vps) for the cello. To generate an E one major third above this lowest C, apply the ratio of 5:4 to get an E of 81.48 vibrations. Transpose this up three octaves by multiplying by eight and the result is 651.85 vps-hardly a comfortable fit with the 660 vps in the violin.

Just Friends

Those are the objective problems with the Just system. Subjective problems exist as well. Many people feel that perfectly tuned Just intervals are emotionally flat and do not give any inference to a line or a chord progression.

The great cellist Pablo Casals was looking for more contour when he spoke of magnetic notes-notes that draw neighboring tones closer to them. Neighboring notes are intonationally influenced by the octave, the perfect fourth, and the perfect fifth. In this scenario, the third step of the scale and the leading tone would be influenced the most, needing to rise to expressively indicate location of the magnetic notes.1 The great cellist Pablo Casals was looking for more contour when he spoke of magnetic notes-notes that draw neighboring tones closer to them. Neighboring notes are intonationally influenced by the octave, the perfect fourth, and the perfect fifth. In this scenario, the third step of the scale and the leading tone would be influenced the most, needing to rise to expressively indicate location of the magnetic notes.1

Casals's concept of centers of tonality that attract neighboring tones finds wide acceptance in the performing community. Delmar Pettys, principal second violinist of the Dallas Symphony and a former member of the Lenox Quartet, prefers to preserve "the personality of the major third and the major seventh." He goes so far as to say that these intervals should be "kind of wild."2 Casals's concept of centers of tonality that attract neighboring tones finds wide acceptance in the performing community. Delmar Pettys, principal second violinist of the Dallas Symphony and a former member of the Lenox Quartet, prefers to preserve "the personality of the major third and the major seventh." He goes so far as to say that these intervals should be "kind of wild."2

John Dalley, second violinist of the Guarneri Quartet, in agreeing with this magnetic note concept, shared with me the research of his teacher, Ottokar Cadek, who, mystified by this clear cultural preference, presented the results of his research into string intonation to an ASTA conference in 1949. In his paper he strove to lift the veil from performing mythology and point the way toward a clear discussion of intonation.3

John Dalley, second violinist of the Guarneri Quartet, in agreeing with this magnetic note concept, shared with me the research of his teacher, Ottokar Cadek, who, mystified by this clear cultural preference, presented the results of his research into string intonation to an ASTA conference in 1949. In his paper he strove to lift the veil from performing mythology and point the way toward a clear discussion of intonation.3

Cadek set out to explain, for his own satisfaction, the apparently random advice he was receiving. He, like many students, was instructed without explanation to tune his thirds and sevenths high. He culled from numerous sources a clear preference for this sort of tuning and then began to search for a deeper reasoning. What he found was a pragmatic tendency on the part of performing artists to err on the sharp side with sharped notes and on the flat side with flatted notes. In major keys this has the effect of raising the major thirds, sixths, and leading tones, and in minor keys it has the effect of lowering the thirds and sixths. Cadek set out to explain, for his own satisfaction, the apparently random advice he was receiving. He, like many students, was instructed without explanation to tune his thirds and sevenths high. He culled from numerous sources a clear preference for this sort of tuning and then began to search for a deeper reasoning. What he found was a pragmatic tendency on the part of performing artists to err on the sharp side with sharped notes and on the flat side with flatted notes. In major keys this has the effect of raising the major thirds, sixths, and leading tones, and in minor keys it has the effect of lowering the thirds and sixths.

Mean Streak

Taking this research one step further, he made the discovery that there was, in fact, a pitch generation scheme that has been with us since the dawn of Western civilization that satisfies these specifications. The ancient Greeks stacked up twelve perfect fifths until returning to an enharmonic of the original tone seven octaves later. This method is known as the Pythagorean system.

The Pythagorean system would share the elegance and balance of the Just system if it were not for one major flaw: the enharmonic arrival tone differs from the equivalent seven octave arrival point by slightly less than one quarter of a semitone. This discrepancy is known as the Comma of Pythagoras, often expressed in cents, or one-hundredths of a semi-tone. This comma of 23.5 cents launched the Meantone industry that dominated keyboard tuning for at least four centuries preceding the dominance of the Tempered system. The Pythagorean system would share the elegance and balance of the Just system if it were not for one major flaw: the enharmonic arrival tone differs from the equivalent seven octave arrival point by slightly less than one quarter of a semitone. This discrepancy is known as the Comma of Pythagoras, often expressed in cents, or one-hundredths of a semi-tone. This comma of 23.5 cents launched the Meantone industry that dominated keyboard tuning for at least four centuries preceding the dominance of the Tempered system.

In Meantone tuning, various distributions of the comma were attempted and promoted by manufacturers and performers of keyboard instruments. Some reigned for a long time, and others passed through vogues of short duration. In the end none of them could compete with the Tempered scale despite the discomfort that tempering has always wrought on sensitive ears. In Meantone tuning, various distributions of the comma were attempted and promoted by manufacturers and performers of keyboard instruments. Some reigned for a long time, and others passed through vogues of short duration. In the end none of them could compete with the Tempered scale despite the discomfort that tempering has always wrought on sensitive ears.

For string ensembles, though, the comma of Pythagoras is of little consequence; the string family's ability to adjust is sufficient to render the comma harmless. What is of use about this pitch generation scheme is not only its tendency to give us variances between sharps and flats-in the required direction, no less!-but the fact that its intervals conform to our pre-existing cultural preferences for wide thirds, sixths, and sevenths.

For string ensembles, though, the comma of Pythagoras is of little consequence; the string family's ability to adjust is sufficient to render the comma harmless. What is of use about this pitch generation scheme is not only its tendency to give us variances between sharps and flats-in the required direction, no less!-but the fact that its intervals conform to our pre-existing cultural preferences for wide thirds, sixths, and sevenths.

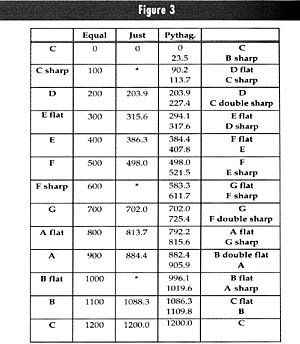

When comparing the various tuning methods, the intervals of the scale are most conveniently expressed in cents. In Equal Temperament, for example, with every half step being 100 cents, the distance between C and C-sharp is 100 cents and the distance between C and D is 200 cents. Figure 3 is an adaptation of this sort of pitch chart generated by Hermann Helmholtz, a nineteenth-century physicist and physiologist. This table makes impractical any attempt to nail down the Just values for the augmented unison, the augmented fourth, and the diminished seventh. Also, some enharmonic values have been inserted in the Pythagorean column for demonstration purposes. When comparing the various tuning methods, the intervals of the scale are most conveniently expressed in cents. In Equal Temperament, for example, with every half step being 100 cents, the distance between C and C-sharp is 100 cents and the distance between C and D is 200 cents. Figure 3 is an adaptation of this sort of pitch chart generated by Hermann Helmholtz, a nineteenth-century physicist and physiologist. This table makes impractical any attempt to nail down the Just values for the augmented unison, the augmented fourth, and the diminished seventh. Also, some enharmonic values have been inserted in the Pythagorean column for demonstration purposes.

Casals was an adamant evangelist for a system of intonation that would clarify note functions. To promote his preferred system he often employed high-powered marketing techniques, using words such as "perfect" and "expressive" to distinguish from the obvious compromises of tempered tuning. Consider, for example, this excerpt from Conversations with Casals by J. Ma Corredor4:

Many people have noticed

your insistence on the prime importance of intonation in performance.

Intonation must be the proof of the sensitiveness of an instrumentalist. Neglecting it is not acceptable for a serious performer and it lowers his standard, however good a musician he may be. It is curious to realize that this concern with good intonation is relatively recent among instrumentalists. When I was young I was stupefied to hear great players like Sarasate and Thompson play out of tune with the greatest ease in the world. In fact, having read many books on the classical period, I have never seen any reference to instrumental intonation, which makes me think that they did not attach much importance to it. And yet I can hardly believe that a composer like Mozart would not have felt the necessity of it. A great genius is always ahead of his time. Intonation must be the proof of the sensitiveness of an instrumentalist. Neglecting it is not acceptable for a serious performer and it lowers his standard, however good a musician he may be. It is curious to realize that this concern with good intonation is relatively recent among instrumentalists. When I was young I was stupefied to hear great players like Sarasate and Thompson play out of tune with the greatest ease in the world. In fact, having read many books on the classical period, I have never seen any reference to instrumental intonation, which makes me think that they did not attach much importance to it. And yet I can hardly believe that a composer like Mozart would not have felt the necessity of it. A great genius is always ahead of his time.

Would you tell me why you use the term "expressive" intonation?

Intonation, as it is conceived today, has such sensitiveness and subtlety that the intonation of [a] note must affect the listener, quite apart from any stimulating accent. The necessity of observing it is understood and observed by all good instrumentalists. In our day, the public would not accept a good soloist if he did not play in tune. Singers are taught "tempered" intonation, but I have noticed that the most gifted and the most artistic ones realize the importance and the subtlety of perfect intonation. The principle I am speaking of is of varied character in its application to string instruments. I make an exception for double-stopped playing: in this case one must compromise between expressive intonation and the "tempered" one. Intonation, as it is conceived today, has such sensitiveness and subtlety that the intonation of [a] note must affect the listener, quite apart from any stimulating accent. The necessity of observing it is understood and observed by all good instrumentalists. In our day, the public would not accept a good soloist if he did not play in tune. Singers are taught "tempered" intonation, but I have noticed that the most gifted and the most artistic ones realize the importance and the subtlety of perfect intonation. The principle I am speaking of is of varied character in its application to string instruments. I make an exception for double-stopped playing: in this case one must compromise between expressive intonation and the "tempered" one.

Is there a marked difference?

I can give a demonstration which would astonish many people: for example I can prove with my system that there is a greater distance between a D flat and a C sharp than there is in a semitone like C-D flat or C sharp-D [see sidebar "How Can This Be?!"]. It is a pity that such an essential part of performance, as this real intonation should be, is still so neglected by some teachers. The other day when I was giving a young pupil his first lesson, I asked him how he had been taught; he said he had been taught intonation from the tempered piano. So you see what work he will have to do to correct this! I can give a demonstration which would astonish many people: for example I can prove with my system that there is a greater distance between a D flat and a C sharp than there is in a semitone like C-D flat or C sharp-D [see sidebar "How Can This Be?!"]. It is a pity that such an essential part of performance, as this real intonation should be, is still so neglected by some teachers. The other day when I was giving a young pupil his first lesson, I asked him how he had been taught; he said he had been taught intonation from the tempered piano. So you see what work he will have to do to correct this!

How do you reconcile "tempered" instruments with expressive intonation?

That is a kind of conflict which is, to me, more apparent than real. In those orchestras which possess great technical perfection and employ some first-class soloists (who practice this subtlety of semi- tones) the conflict does not arise, which proves that the "fusion" between the "tempered" instruments and expressive intonation is perfectly possible. That is a kind of conflict which is, to me, more apparent than real. In those orchestras which possess great technical perfection and employ some first-class soloists (who practice this subtlety of semi- tones) the conflict does not arise, which proves that the "fusion" between the "tempered" instruments and expressive intonation is perfectly possible.

You told me of the painful impression you get on hearing very good performers who are satisfied with the approximate intonation.

Yes, if an instrumentalist misses some difficult part of a passage, that does not influence my judgment, but I must say that I cannot forgive an approximate intonation in a so-called artistic performance. I want to feel that the performer has a constant care for perfect intonation which reflects his musical sensitiveness. Yes, if an instrumentalist misses some difficult part of a passage, that does not influence my judgment, but I must say that I cannot forgive an approximate intonation in a so-called artistic performance. I want to feel that the performer has a constant care for perfect intonation which reflects his musical sensitiveness.

It must be very difficult to acquire perfect intonation for a student of a string instrument!

Of course it is, and I feel convinced that it should be dealt with at the beginning of his studies. Either because of insufficient listening power or through having contracted the habit of compromise, which is "tempered" intonation, the student will need to undergo a "cure" for his aural sense. Only yesterday I had the joy of seeing a pupil of mine, after long explanations and demonstrations, beginning to realize how much better he could hear the exact sound. The effects of any neglect of this kind at the beginning of studies (which is very frequent) can affect a player through the whole of his career, however gifted he may be. Of course it is, and I feel convinced that it should be dealt with at the beginning of his studies. Either because of insufficient listening power or through having contracted the habit of compromise, which is "tempered" intonation, the student will need to undergo a "cure" for his aural sense. Only yesterday I had the joy of seeing a pupil of mine, after long explanations and demonstrations, beginning to realize how much better he could hear the exact sound. The effects of any neglect of this kind at the beginning of studies (which is very frequent) can affect a player through the whole of his career, however gifted he may be.

Back To The Future

Casals' exhortations to instill a more sensitive and flexible sense of intonation at an early age must be embraced by every teacher. But really now, can a seven-year old be expected to listen with rapt attention while her teacher sketches out a shimmering mathematical tapestry of intonation theory? Probably not, and that is why a three-tiered approach to this method of listening and tuning is best.

In the first stage, with pre-reading students and the very young, leading tones are not too difficult to identify. Teachers can stress that the leading tones lean as much as possible into the tonic. After the leading tones, the next candidates are major thirds or "happy notes" to distinguish them from "sad" minor thirds. With a little bit of coaxing, they could all be given appropriate color. In the first stage, with pre-reading students and the very young, leading tones are not too difficult to identify. Teachers can stress that the leading tones lean as much as possible into the tonic. After the leading tones, the next candidates are major thirds or "happy notes" to distinguish them from "sad" minor thirds. With a little bit of coaxing, they could all be given appropriate color.

After the student has learned to read music, the second stage is to encourage the raising of sharps and the lowering of flats. This can be dealt with easily enough by using the age-old technique of teaching the student to rely on printed accidentals for guidance. After the student has learned to read music, the second stage is to encourage the raising of sharps and the lowering of flats. This can be dealt with easily enough by using the age-old technique of teaching the student to rely on printed accidentals for guidance.

Obviously, the key of C major is of little help. It is best to begin with a key such as D major. Have the student play a scale in D major and alter the tuning of the F-sharp and the C-sharp in the direction of the arrows, as notated in Example 1. The third and leading tone have now been painlessly raised. Obviously, the key of C major is of little help. It is best to begin with a key such as D major. Have the student play a scale in D major and alter the tuning of the F-sharp and the C-sharp in the direction of the arrows, as notated in Example 1. The third and leading tone have now been painlessly raised.

This mechanism can also be demonstrated with the flatted keys, as long as teachers are not intimidated by wrestling with the metaphysical question of whether or not a tonic can be lowered. B flat major is a very clear example, as shown in Example 2. This mechanism can also be demonstrated with the flatted keys, as long as teachers are not intimidated by wrestling with the metaphysical question of whether or not a tonic can be lowered. B flat major is a very clear example, as shown in Example 2.

With a C harmonic minor scale, the teacher can point out the beneficial aspects of lowered flats and the corrective B-natural, as shown in Example 3. With a C harmonic minor scale, the teacher can point out the beneficial aspects of lowered flats and the corrective B-natural, as shown in Example 3.

But string teachers will not have traveled very far in this narrative if they end up teaching a bunch of rules without any underlying logic. At the beginning of the story, the confused Ottokar Cadek-a stand-in for the huddled, confused masses of string students everywhere-wandered about in a search of his intonational roots. In teaching, as in politics, the price of ungrounded pronouncements is either rebellion or brainless herd behavior. The third and final stage of the process must be the revelation of all the elements of mathematics, history, and culture. The student thus enlightened can take up the mantle of Pythagoras and ride away a champion, spreading justice and reason throughout chamber music. But string teachers will not have traveled very far in this narrative if they end up teaching a bunch of rules without any underlying logic. At the beginning of the story, the confused Ottokar Cadek-a stand-in for the huddled, confused masses of string students everywhere-wandered about in a search of his intonational roots. In teaching, as in politics, the price of ungrounded pronouncements is either rebellion or brainless herd behavior. The third and final stage of the process must be the revelation of all the elements of mathematics, history, and culture. The student thus enlightened can take up the mantle of Pythagoras and ride away a champion, spreading justice and reason throughout chamber music.

This small candle in the dark corners of intonation demonstrates that, when it came to intonation, many beliefs of bedrock certainty were either totally opposed to other bedrock ideas or not intellectually aligned with the individual's practice. How many of us have met the musician who strenuously argues that tempered thirds are flat and they like to hear the more lively Just intonation? This small candle in the dark corners of intonation demonstrates that, when it came to intonation, many beliefs of bedrock certainty were either totally opposed to other bedrock ideas or not intellectually aligned with the individual's practice. How many of us have met the musician who strenuously argues that tempered thirds are flat and they like to hear the more lively Just intonation?

More knowledge and a lot less certainty should infuse these discussions. Like all of the techniques of the art of music making, intonation is a tool. Whereas Pythagorean tuning will help quartets to accommodate the intrinsic problem of the low C and the high E, players must keep in mind the adage: "When all you've got is a hammer, everything looks like a nail." Some situations will render Tempered intonation preferable to Pythagorean, or maybe what really needs to be heard at a certain point is a chord that is perfectly at peace in a Just universe. As important as listening to pitches is to attaining good intonation, that skill is secondary to listening to what those around you are playing and saying. AST More knowledge and a lot less certainty should infuse these discussions. Like all of the techniques of the art of music making, intonation is a tool. Whereas Pythagorean tuning will help quartets to accommodate the intrinsic problem of the low C and the high E, players must keep in mind the adage: "When all you've got is a hammer, everything looks like a nail." Some situations will render Tempered intonation preferable to Pythagorean, or maybe what really needs to be heard at a certain point is a chord that is perfectly at peace in a Just universe. As important as listening to pitches is to attaining good intonation, that skill is secondary to listening to what those around you are playing and saying. AST

References

1. J. Ma Corredor, Conversations with Casals (New York:F. P. Dutton

& Company/ Penguin Books, 1957).

2. Delmar Pettys, interview with author November 18,1995.

3. Ottokar Cadek, paper read at the MTNA/ASTA String Forum,

Chicago January 1, 1949.

4. J. Ma Corredor, Conversations with Casals (New York: F. P.

Dutton & Company/Penguin Books, 1957).

|

|